The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

31 October 2016 | By

Originally for Colta.ru

• In Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Man of the Crowd (1840), a man in London watches individuals in a crowd until he sees one who is so peculiar he decides to follow him.

• In Fritz Lang's film, M (1931), beggars in Berlin form an unofficial surveillance network to watch out for a killer of children.

• In Alfred Hitchcock's film Rear Window (1954), a man who is stuck in his room because of an injury starts watching his New York neighbours in their own apartments.

• In Francis Alÿs's Doppelganger (1999-present), when the artist arrives in a new city, he watches the crowd until he finds a person who looks like him (a term he interprets in various ways), then walks with them.

• In Michael Haneke's film Caché (2005), a bourgeois Paris family is sent video taken by an anonymous person who is watching their apartment.

• In Olga Chernysheva's series of photographs titled On Duty (2007), staff on the Moscow metro watch passengers on the escalators.

The act of watching people is woven into narratives of the modern city; these are just a few of many hundred examples. There are even more stories involving state surveillance of the individual and the crowd, from philosopher Jeremy Bentham's plan for a model prison based on an all-seeing Panopticon to the host of science-fiction stories about authoritarian societies, for which Yevgeny Zamyatin's We set the pattern.

When the state is responsible for surveillance, the aim is generally to detect criminals, dissidents or terrorists – in other words, to find its enemies; when the individual is acting on their own their motivation is likely to be more ambiguous. In The Man of the Crowd, for example, the narrator begins watching people through what seems like idle curiosity. One hundred and sixty years later, in Christopher Nolan's film Following (1998), a young man will start following people through the London streets in the hope of breaking his writer's block. In both stories, the process of watching becomes something more frightening for the watcher. In the latter, he is drawn into participating in a story of crime and violence by the person he is watching. In the former, the city pulls the watcher into a dark compulsion that keeps him moving through its streets for 24 hours without sleep. The city is depicted as teeming with anonymous others, a crowd which is at first a playground for the idle watcher, then a trap.

At the same time, psychology researchers have been finding that paranoia, psychosis and paranoid schizophrenia are far more common in urban dwellers – and for the first time in human history, half of us now live in urban areas, bringing with it an increase in paranoia and delusions of persecution. The pace of life in the city and the number of unknown others – forcing us to avoid, confront or negotiate encounters and conflicts on a daily basis – appear to be a source of tremendous psychological pressure. The urban crowd is full of strangers who may turn out to be enemies. But is the enemy the watcher or the watched?

The Demolition Project, a collaboration between Russian artist Alisa Oleva and British writer Debbie Kent which uses the city as both workshop and material, set out to explore these undercurrents and tensions between the solitary walker and the crowd. Inspired by Alÿs as well as Vito Acconci's Following Piece (in which Acconci follows random strangers through the streets of New York) and Sophie Calle's Suite Vénitienne (the artist documents her surveillance of an individual in Venice) and The Detective (she hires a detective to follow her through Paris for a day), we began following strangers in the crowd and developed two pieces of work inspired by this: an audio walk, Follow Me, and a participatory piece, Shadow. Taking this work to workshops and events in London and Berlin threw up many ideas for us around who is watched and who watches.

At the same time, signs began appearing everywhere on London's transport network seeming to invite the general public to put each other under surveillance. And there has been a constant drip-feed of warnings through the media to the public to be “vigilant” against suspicious behaviour, whatever that is.

We tend to think of watching the crowd in the 21st century as something associated with technologically mediated mass surveillance – CCTV cameras, drones, facial recognition software, algorithms that map suspicious movement patterns. This is certainly something the art world has engaged with – for example, Manu Luksch with her 2007 CCTV-footage film Faceless, Emily Jacir with webcam stills in Linz Diary (2003), and Broomberg and Chanarin with facial recognition software in Spirit is a Bone (2014); as well as others whose work proposes a defence against surveillance, such as Zach Blas's Facial Weaponisation Suite (2011-2014). This is one strand of our interest. But the state's injunction to watch each other has an insidious power, generating fear and suspicion of life in public spaces which we were interested in exploring.

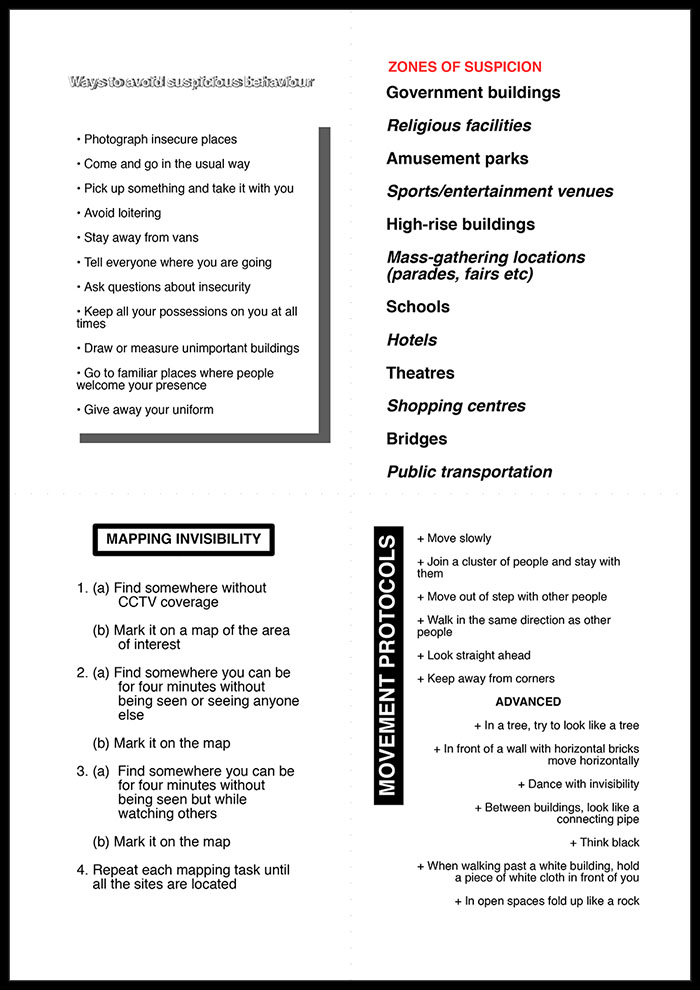

A friend of ours, artist Simon Farid, challenged us to find places to hide both from CCTV and from the eyes of others, and we found how impossible that is to do in a city like London. We became interested in how to be invisible in the city – to evade the eyes of others, and to watch and assess their behaviour of the crowd. We looked for advice and found it in guidelines from the security services: from London's Metropolitan police, the Los Angeles police department, the CIA and other sources. We started to research our ideas about engaging with the surveillance city through “walkshops” – walking workshops that take place on the street – in various parts of east and central London, including one made specially for a gallery, Calvert 22, which has been running a season on Power and Architecture.

Our attempts to observe the suspicious behaviour of the crowd have made us feel as if we are the strangest, most suspicious people around – by taking pictures, filming CCTV cameras, making notes, indulging in “unusual activities” and “strange comings and goings” we are a perfect fit for the police's description of potential terrorists. It is not necessarily an unpleasant experience. Our explorations have so far highlighted for us how far the city is a panopticon, with eyes everywhere (whether human or digital). Do we develop tactics to defend ourselves against this – or do we embrace suspicious behaviour? We realised that this ambivalence is embedded in the heritage of walking the city. In Passagen-Werk (in English The Arcades Project), Walter Benjamin's collage of notes, quotations and observations on the origins of modernity in 19th century Paris, the status of the flâneur is described – the man who wanders through the city streets observing urban life: “on one side, the man who feels himself viewed by all and sundry as a true suspect and, on the other side, the man who is utterly undiscoverable, the hidden man”.

We were also interested in proposing something that would be open to everyone walking in the city, the site where suspicious behaviour is both performed, observed and created by the fears of the observer. We decided to generate and scrutinise urban paranoia through the means of an audio walk or app, a project we are currently developing. We imagine people everywhere will soon be using this essential accessory: a voice in the ear that tells you how to monitor suspicious behaviour in public spaces – not least your own behaviour.

For those who want to embrace or explore suspicious behaviour before our work is realised, we can share some of the tasks here, in the sheet attached that can be printed out and folded into a booklet to carry with you.